"A Dream, We Once Had" : How "Smart City" Movement Becomes Another Tool of Extraction

This piece is the second part of a trilogy essay.

It always has something to do with screens.

The new capital had one for almost two years now, a command center with glossy LED displays and ambient light, as if national dignity could be coded into color temperature. Bandung had one earlier, introduced by a then-rising star of “tech-savvy” leadership. Surabaya followed. Gradually, one after another municipalities join the aesthetic arms race. Screens go up. Budgets get approved. Media releases circulate. Progress, finally, has a room. Makassar Municipality even calls it “WAR ROOM”.

But when you step inside one of these rooms, you don’t really hear the city. You can “watch” a few CCTV feeds up and running like they do in Hollywood pictures, with similar level of functionality (minimum to none, granted both funtion as a show, so...). But what you can actually do is hear the hum of air conditioners and bright silence. Outside, at the urban territory, the drains are still clogged. The footpaths are broken. The floods are worse. The angkot driver is still shouting at rush hour. None of that bleeds into the screens. The screens and the walls are squeaky clean.

This is the most important thing to understand about Indonesia’s “smart city” obsession. Started a decade earlier and now having the legal foundations (such as Perpres 95/2018 tentang SPBE, Perpres 39/2019 tentang Satu Data Indonesia), it has been a performance, not a reform. The rooms are designed to be photographed with the leadership admired in front of a dashboard. The term “smart” became a shortcut for legitimacy. It doesn’t mean the city works better. It just means the city looks modern enough for a publicity.

For years, “smart city” appeared in planning documents, budget plans, and procurement packages across dozens of cities. Mayors fetishized it, startups sold it, government officials praised it. But ask what it actually means, and the answers collapse into slogans. “Efficiency.” “Connectivity.” “Digital innovation.” Rarely do we hear the substances: justice. Fairness. Equity.

This is not accidental. The origin of the term never promised those things. “Smart city” first came from tech vendors, international consultants, and multilateral banks. It was about infrastructure efficiency. Better lighting, quicker reporting, and optimized logistics. Even in itsearliest global form, it had nothing to do with dignity. It was about better control. And in Indonesia, that control became aesthetic. It became a series of screens covering the walls.

But real progress is rarely screen-friendly. Jakarta’s best digital innovations, like the Jaklingko integrated public transport fare system or the Jakarta Satu spatial data platform, rarely trend. Because they’re not flashy. They’re not invoking the similar digital fever to the other cities because they don’t make good ribbon-cutting events. They’re slow, policy-driven, often invisible. And yet, however imperfect, they’re the ones that actually (at least trying to) shift how the city operates for the better.

Yet most of the attention flows elsewhere, to the command rooms, the AI conferences, the new tax software. The ones where “smart” is said louder than it is understood. Where technology is promised before any understanding of what people actually need. Where the city is watched, but never really cared for.

This is how Indonesian cities have come to govern. Not by resolving problems at their roots, but by digitizing them. Making the problem easier to observe, not necessarily meaning the follow up to those observations are imminent. It’s not that these tools are entirely useless, sometimes, they help. But they often serve as stand-ins for real decisions. A distraction. Performing progress and saying “we are working”.

Digitalization here is not transformation. It is delay in high resolution.

Because instead of fixing food insecurity, we create a new e-wallet for subsidized rice. Instead of investing in walkable streets, we install cameras for traffic violations. Congestion becomes a livestream; healthcare becomes a QR queue. And by the time the problem reaches the screen, it’s already terminal. We’re just watching it in sharper definition.

What’s more, this fetish for tech doesn’t emerge from necessity. It grows from procurement culture. From the need to show movement. Visible, expensive, grandeur movement, even if nothing fundamentally changes. Instead of paying teachers adequately or providing public transportation, municipalities buy wares, both hardware and software. The software has updates. The updates need training. Training needs consultants. Consultants need presentations.

It becomes a cycle where technology replaces responsibility. The city doesn’t need to get better; it just needs to look like it’s trying. And when all this happens without a moral compass, without a design for fairness, it ends up accelerating the very inequality it should’ve helped address.

That’s the thing about efficiency. It’s only a virtue when it serves something just. But in many of Indonesia’s smart city programs, efficiency has become the goal itself. Faster complaints. Faster data processing. Faster ticketing. As if speed could replace result. The question is, faster toward what?

Who actually benefits when a report gets filed faster, if street holes never gets fixed?

Who gains when a poor family can register for public housing via app , if the housing doesn’t exist?

Efficiency has no conscience. It follows the strongest currents. And when that current is profit, not justice, the ones who lose are the ones who cannot keep up.

You can see it everywhere: in the way digital payments shift transaction costs onto small vendors. In the way QRIS fees quietly skim the margins of a grandmother’s banana stall. In the way ride-hailing apps allow surge pricing during rain and floods, while passengers curse the drivers and not the government that left them no other option.

The systems may seem “smart.” But they’re not fair.

Because fairness, real fairness, is friction. It takes time. It requires pause, attention, redistribution. It is not scalable. It’s messy and it doesn’t make a good press release.

Which is why it gets left behind.

It’s easy to forget that technology is a business. That software has a vendor. That every “smart” system comes with contracts, renewals, service agreements, and line items buried under acronyms.

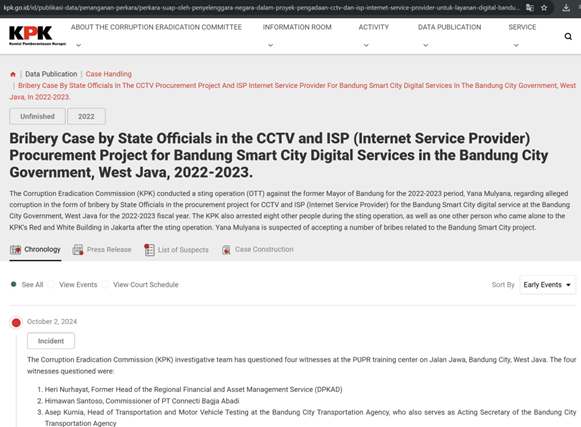

Smart city programs in Indonesia are rarely about systems reform. They’re about procurement. The same old logic as building a flyover or a government tower, but now with UX mockups and facial recognition plugins. The budget shifts from concrete to code, but the incentives remain. There’s still a tender and budget markups benefitting everyone but the public.

This is why the smart city narrative spreads so well. Not because it’s flawless, but because it sells. It speaks in the same transactional language our bureaucracy understands: visible spending, easily claimed credit, and plausible deniability when it fails. And when it does fail, there’s always a newer system around the corner to replace it. A fresh project hungry for a bigger budget.

In this kind of society, equity doesn’t stand a chance. Equity asks the opposite: to slow down, to audit, to consider who benefits and who doesn’t. Equity isn’t an app, it’s neither sexy nor photogenic.

Yet equity is the only thing that makes a city just. It’s the only thing that ensures services go where they’re needed, not where they’re easiest to deliver. Yet because it cannot be procured, it is perpetually sidelined. And so the cities get smarter instead of kinder. Faster, but not fairer. Louder in their announcements yet hollower in their impact.

The word that disappears in all this , the word no politician wants to say aloud , is “equitable.”

Not global, not modern. Equitable.

It’s a difficult word, and deliberately so. Because equity requires confrontation. It demands that we face what we’ve ignored: who gets left behind, who pays for progress, who isn’t invited to such exclusive future we build. It forces us as a society to admit that we have been mean to exclude our neighbours, our elders, our children, in order to find a fair solution. (But that would hurt our feelings and eastern values now isn't it? Because we are so kind to each other, am I right?)

An equitable city would never design a system that charges fees to a street vendor making four dollars a day. It wouldn’t block the poor and elderly from accessing healthcare with an online-only queue they can’t navigate. It wouldn’t normalize the treatment of workers , cleaners, drivers, security guards , as less deserving of dignity, simply because their jobs don’t come with passwords and ID cards.

But here we are. Building dashboards while the foundations crack. Pointing to QR code payment adoption as innovation, while our currency weakens by the hour and the public education system that could’ve taught digital literacy in the first place remains underfunded. Talking about AI in televised speeches while hospitals can’t print a patient chart on time.

A city can call itself smart all it wants. But if its people are exhausted, extracted, and excluded, then smartness becomes a lie told in the language of contracts.

No one voted for this system. But everyone has learned how to live in it.

We didn’t decide that ride-hailing should replace public transport. That elderly vendors should carry QR codes taped to their carts. That digital bureaucracy should require PDFs, screenshots, apps, OTPs, logins, retries, resets. No one designed this as a whole. Yet it unfolded , one frictionless decision at a time.

And so, people adapt. They learn the interface. They memorize the hack. They search for loopholes and copy-paste answers into live chats with bots. When the system is extractive and brittle, survival becomes its own kind of literacy. You don’t demand change , you become good at workarounds. Efficiency becomes a form of submission.

Some adaptations are practical, others are corrosive. And along the way of each of us trying to find “hacks” in our daily life, sometimes we end up extracting from each other.

The driver who turns off his app during rain and asks for triple the price , he's not greedy. He’s just responding to a system that treats his time as disposable and his effort as cheap. The consumer who gets angry at delays isn’t entitled. They're reacting to the endless promise that "smart" equals "instant."

And then, somewhere along the way, the line blurs. Between urgency and cruelty, between adaptation and acceptance.

This is how inequality becomes invisible. Not because it disappears, but because it is normalized. Turned into UX, into fee structures, into "terms and conditions."A society that once lived horizontally , neighbors, traditional markets, shared food, shared grief , now climbs over each other for the illusion of “better.” The vertical life replaces the collective one. Everyone tries to move upward on top of each other without looking sideways and around them.

And what do we build to support this? Systems that count, but do not care. We track movement, log payments, verify location. We know who took which train at what time, but not why he couldn’t afford a bottle of water while riding it.

It is obedience instead of intelligence.

It is a system where we measure more and understand less. Where progress is defined by signal strength, not moral strength. Where we pretend optimization means improvement, because it’s easier than asking what, or who, is being optimized out.

Good luck on your Monday.